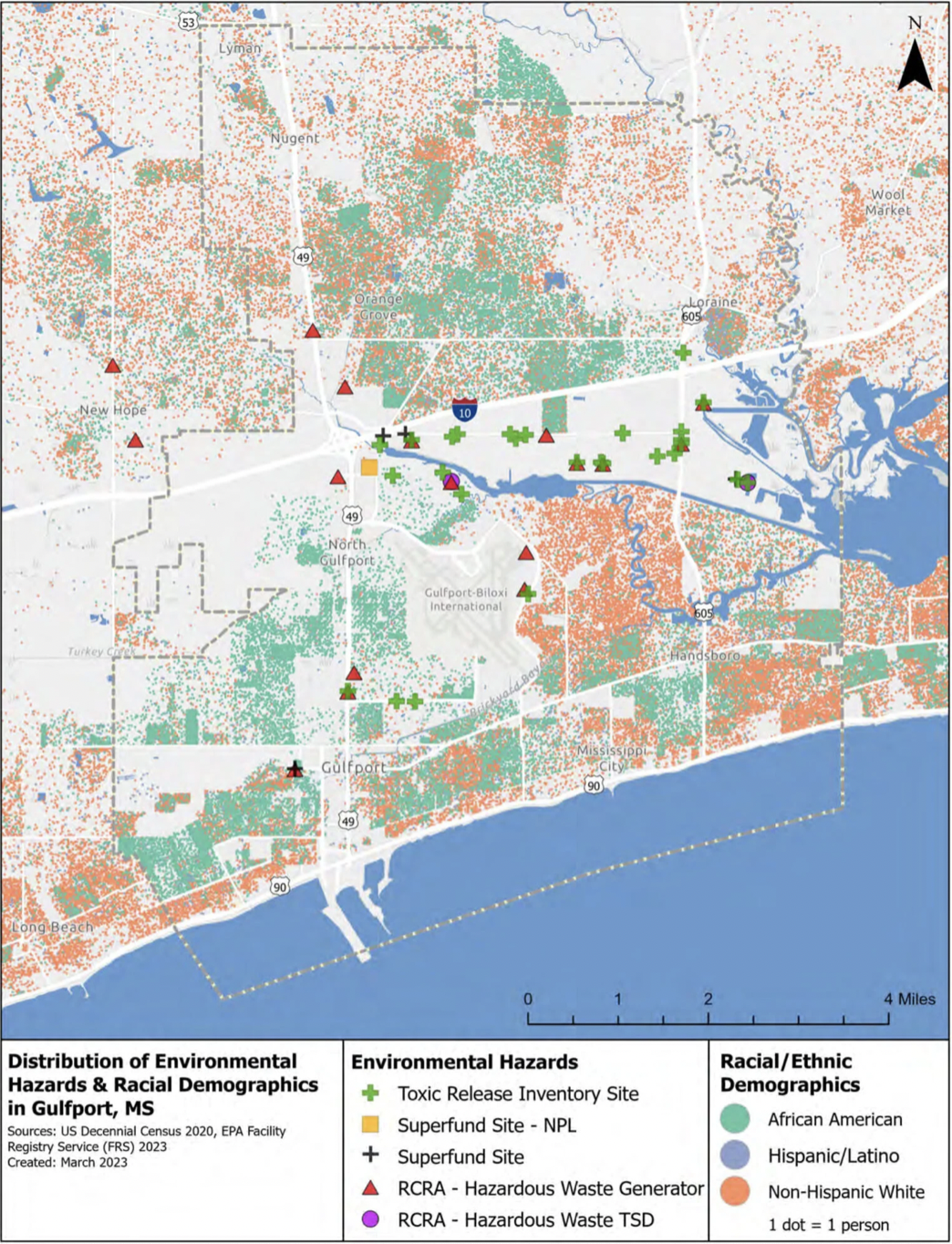

Residents and activists in three predominantly Black neighborhoods of North Gulfport say a proposed military equipment storage site could bring dangerous effects for both the community and surrounding ecosystems.

In a lawsuit filed jointly between the American Civil Liberties Union of Mississippi and environmental law firm EarthJustice, critics of the project point to the possibility that explosive ammunition could be stored at the development, which is within a mile of dozens of homes. They also express concern that the depot will be built on the site of a former fertilizer plant where samples of arsenic and lead in the soil exceed regulatory limits, and along a waterway that those chemicals could pollute.

The suit, now set to be heard in appeals court after being deferred by the Mississippi Supreme Court, says the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality’s permit board issued a Clean Water Act Section 401 permit — which affirms that a development’s discharge into nearby waters meets water quality standards — erroneously and without following internal regulations established by state law, such as determining whether explosive ammunition will be stored at the site or conducting an alternative site analysis.

The decision would determine whether the permit board followed all rules and regulations required of it when determining whether to grant or deny such a permit application, and could set a legal precedent for the future of the permitting process within MDEQ.

"When the permit board did not follow the appropriate laws and regulations it resulted in a situation where a military installation is proposed to go into historically Black community, without anyone during the permitting process or during the review process or during the public comment process ever knowing about important aspects of that potential use,” said Joshua Tom, legal director at the ACLU of Mississippi and co-counsel on the case.

“And one of those aspects is potential storage of military explosives in your community that the permit board never noticed, never analyzed."

According to the suit, the possibility of explosive ammunition being marshaled at the development was not included in a series of public notices provided to residents of the historic community, nor were other locations justly considered, such as at the current Port of Gulfport or the downstream Industrial Seaway.

Environmental hazards like contamination and increased flooding are among some of the biggest concerns that residents and advocates have in the historically Black community, where more than 150 years of culture developed under segregation and Jim Crow-era laws is now at risk.

“We’re talking about a part of town that is overburdened and already has more hazards than other parts of town,” said Rodrigo Cantu, a senior attorney at EarthJustice’s Gulf Regional office.

There is still not a clear answer from MDEQ or the Department of Defense as to whether explosive ammunition will be stored at the site, and between the dual threats of that possibility and increased flooding, a community which began as a refuge for emancipated African Americans along Mississippi’s coast is now seeing the portents of an exodus.