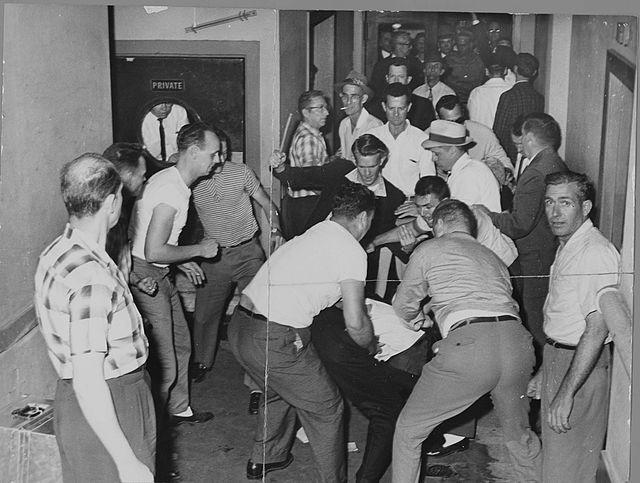

They were met with more and more opposition the further South they got and the group’s strategy of civil disobedience would be tested. Theyarrived in Alabama on May 14, Mother’s Day.

“We got beaten twice that day,” said Charles Person, the youngest of the Freedom Riders and author of the memoir “Buses Are a Comin’.”

He remembers vividly when they weremet by an angry white mob at a Greyhound bus station.

“We got beaten on the bus in Anniston, then they rode with us to Birmingham,” said Person. “They taunted us all the way, called us every name you can think of and they did that for two hours.”

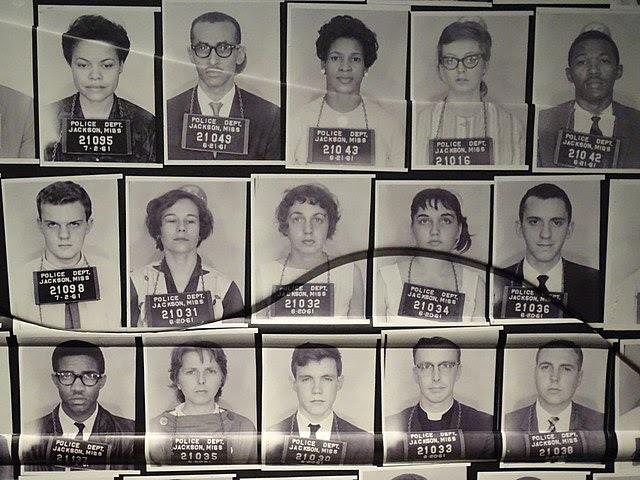

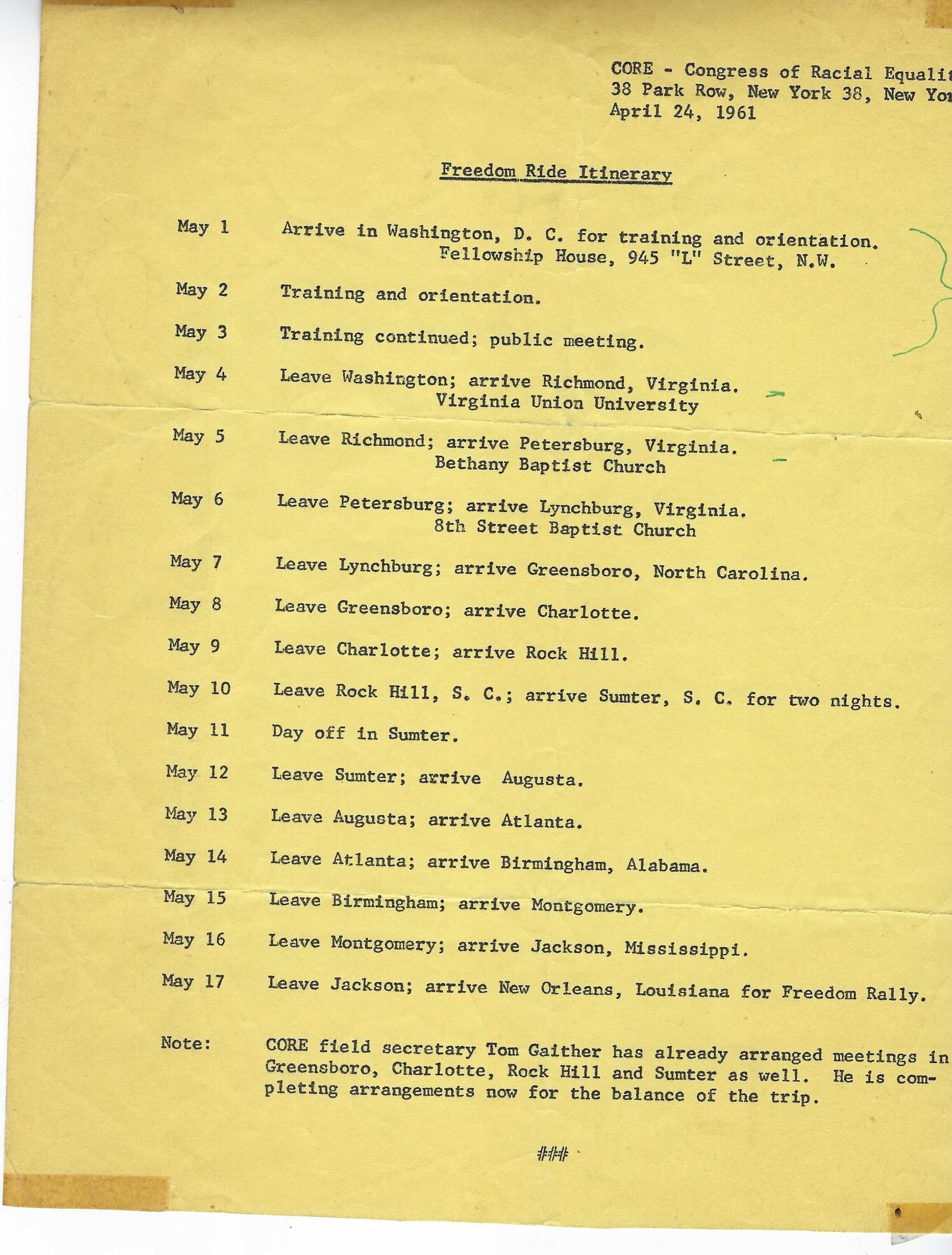

Person, who was 18 at the time, was chosen and trained by the Congress of Racial Equality,CORE, which practiced nonviolent protest strategies.

As Person was beaten that day, he said he felt no pain.

“We didn't even block punches. We took their best shot,” he said. “And also, if you hit the ground, they instructed us to take the fetal position, so you protect your vital organs.”