The United Auto Workers was on a historic six-month run until it got a reminder that when it comes to unions, southern hospitality often gets replaced with hostility.

The UAW’s union dreams seemed unstoppable. Then came the realities of the South

The United Auto Workers was on a historic six-month run until it got a reminder that when it comes to unions, southern hospitality often gets replaced with hostility.

Gulf States Newsroom

The UAW’s union dreams seemed unstoppable. Then came the realities of the South

It started last November when the UAW ended decades of concessions to carmakers by ratifying record contracts at Ford, GM and Stellantis. The success inspired southern auto plant workers to launch their own campaigns, starting at Volkswagen in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Volkswagen employees kept the momentum going when they voted overwhelmingly in April to join the UAW — a victory a decade in the making. Suddenly, the dream of unionizing auto workers across the South seemed possible.

Then, along came Alabama.

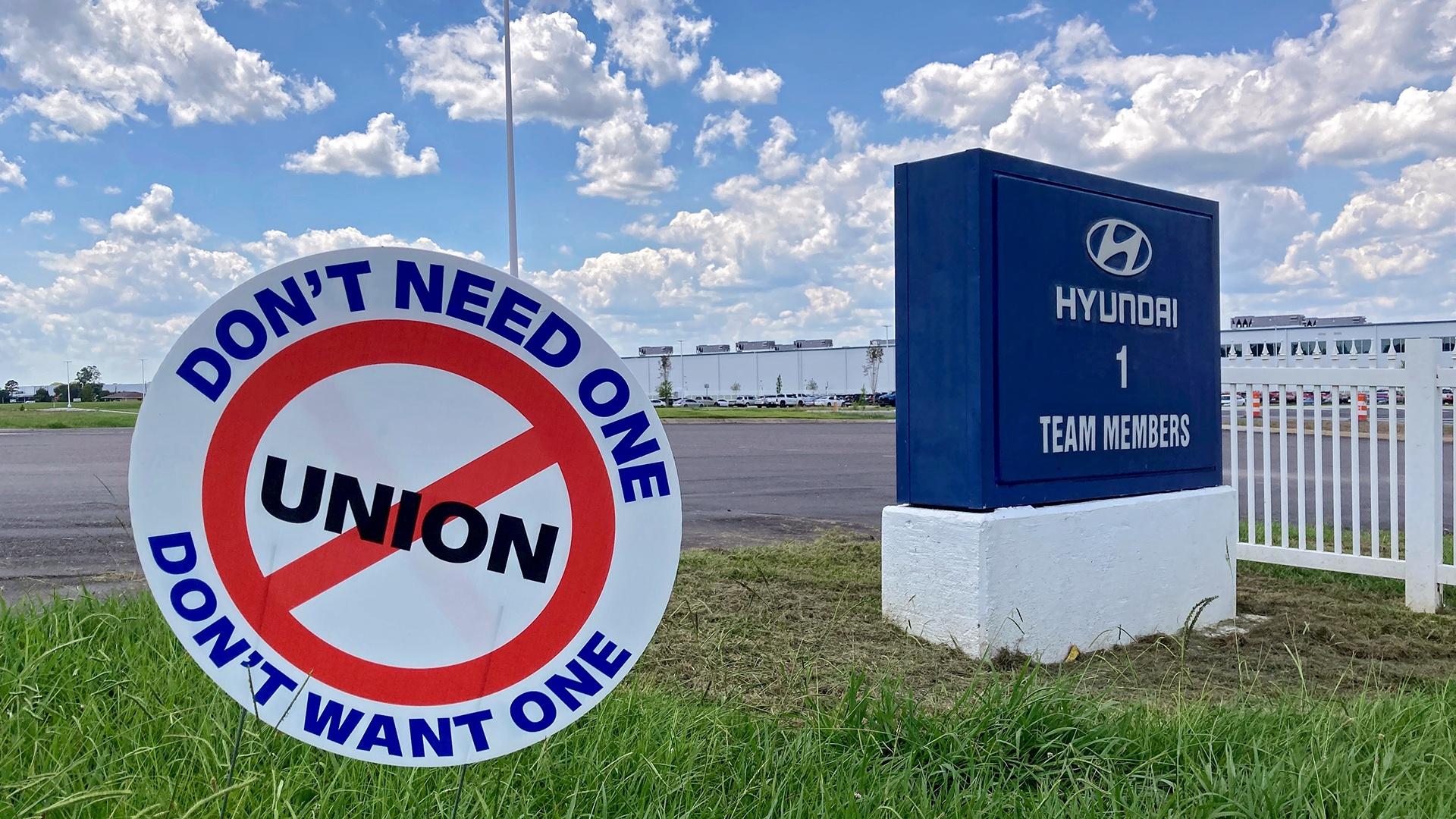

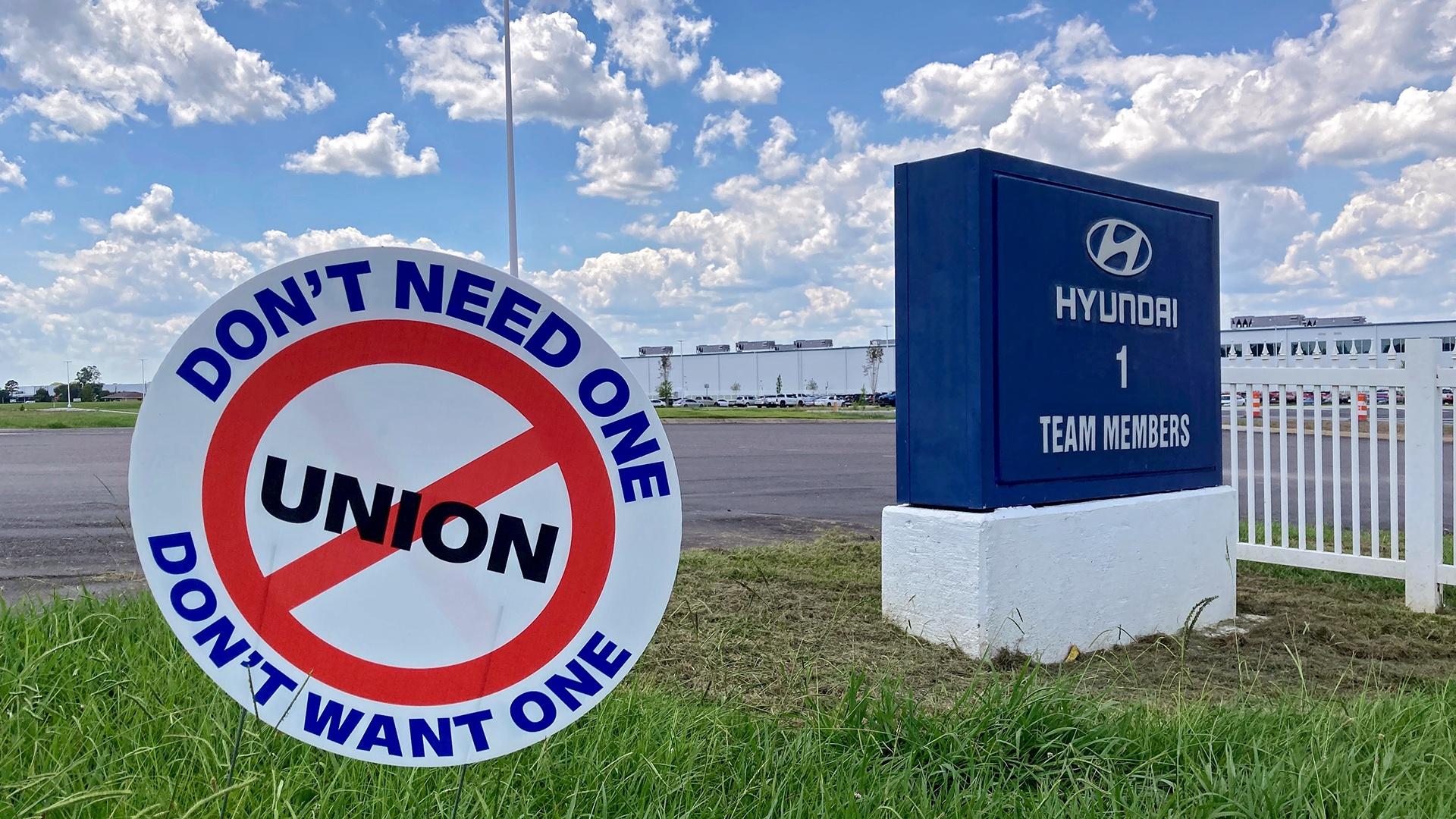

A Mercedes-Benz plant in Vance, Alabama, and a Hyundai plant in Montgomery, Alabama, soon joined the movement. But just one month after the historic win in Chattanooga, Mercedes workers voted against unionizing. Before that vote, one organizer predicted the Hyundai plant would have a union election by the end of the summer. But since then, none have been scheduled.

Adding to the UAW’s woes is a federal investigation into its leader, Shawn Fain, that threatens to tarnish the rehab work he’s done on the organization’s reputation — forcing the UAW’s southern campaign efforts to shift from the fast lane to a slow one.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey likes to say there is no “Sweet Home Alabama” for the UAW. That’s certainly true in Montgomery.

In fact, the UAW could not find a landlord in the capital city willing to rent the union space for a headquarters. A lease was drawn up for one rental before it was taken back when the business discovered who the lease was for. Now, the building sits boarded up on South Boulevard.

“They’d rather board up their business than allow the UAW to lease the building,” Antonia McClain, a UAW organizer, said. Campaign headquarters are now located just south of the city, in a first-floor room at the far end of a Fairfield Inn.

The Alabama opposition comes from business leaders, politicians and even preachers. Hyundai hasn’t been shy about joining the conversation either, posting articles and videos online, on the app workers use and on screens in the factory.

All the groups share a similar message: Hyundai is great for Montgomery. Why ruin it by bringing in a union? Why invite outsiders in when workers are paid well, especially by Alabama standards?

Mercedes management in mid-July doubled down on the pay talking point by announcing a $3 per hour raise for workers at its Alabama plants, according to employees. A Mercedes spokesperson would not confirm or comment on the bump.

The move appears to be management making good on promises made during the tense campaign to improve the plant if workers turned down the union. It also fulfills a demand pro-union workers made to end what they called the “Alabama Discount,” where they were paid less than unionized workers in the north. Once this pay bump is in effect in late October, top pay at the plant floor will be just below those at unionized GM plants, according to the UAW.

But pro-union employees said the credit for those wage increases should go to the UAW.

Before it started its strikes against America’s Big Three automakers, Alabama workers received less than $3 per hour in raises over the past decade, according to the union. Since then, wages have been raised by $9.50 per hour.

“Everybody knows everything that’s taken place has been because of the union,” Mercedes line worker Sammie Ellis said, who still wants to see improvements to retirement and insurance benefits. “That’s undeniable.”

The UAW is also taking credit by saying Mercedes told workers it could not provide raises while the union is charging the car maker with violating labor laws. UAW President Fain reportedly sent a letter in June to the German Works Council to intervene. The raises at Mercedes were announced a month later.

Fain has long been seen as the counterpoint to another argument the Alabama anti-union crowd has made: That the UAW is corrupt.

A federal investigation has led to multiple UAW presidents going to prison for various reasons, including embezzling union funds. Fain was seen as a clean break from that corrupt past.

But a federal monitor put in place because of those investigations is now looking into whether Fain has abused his power. A recent report by the monitor said the UAW recently ended a “period of its history characterized by a culture of fear and reprisal,” but parts of that culture still exist in the union.

Pro-union Hyundai workers say the investigation has rarely been discussed at the plant, though Hyundai has put out posts and videos about it. But the UAW’s reputation, which directly led to the Hyundai campaign’s official start last February, is no longer being leaned into as a recruitment tool.

Hyundai Quality Inspector Quichelle Liggins said she doesn’t lead with the UAW name when recruiting her co-workers, focusing instead on trying to educate them on what a union does.

“The famous saying is, ‘Put it where the goats can get it,’” Liggins said. “I can’t talk to them from the UAW standpoint. I have to start with the basics. A union is people coming together, in getting their voice heard, negotiating a contract.”

Still, the union has a chance to recapture its lost momentum.

The UAW knows it must negotiate a strong contract at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga. That’s still in its early phases, with the union’s bargaining committee elections set for the end of July.

The goal is to negotiate the kind of contract with pay and benefits that will make other southern workers jealous enough to want their own union.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.