According to the most recently available U.S. Census data, Holmes County's poverty rate of 39.2 percent makes it one of the nation's poorest. But it's also home to the nation's third highest population of residents who are Black, and a rich history of Civil Rights organizing personified by figures like Fannie Lou Hamer and Hartman Turnbow.

The DOJ investigation follows an earlier federal lawsuit and several complaints from Black residents who say they've endured brutality, extortion, retaliatory arrests and corruption for more than two years.

The complaint was filed by JULIAN, a national civil rights organization with a special focus on Mississippi and discriminatory policies, who also filed the original complaint against Lexington police which is set to be heard by a federal court this June.

Its founder, attorney and advocate Jill Jefferson, was herself arrested by Lexington officers only days after attending a closed-door DOJ listening session which allowed several residents to share their experiences with officers in the town.

Kadin Love, a regional organizer at Julian, says this complaint hopes to put on display the systemic nature of policing in the town.

“We had hoped that perhaps the DOJ investigation would slow down some of the police misconduct that was going on in Lexington. But it appears that it is continuing even as the DOJ is investigating,” he said. “I think the fact they decided to continue even after they began investigating just shows the level of impunity that the police are showing in terms of this investigation.”

In the past two years Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke, head of the DOJ's Civil Rights Division, has led investigations into alleged systemic police misconduct in large cities like Phoenix and Baltimore, where they closely observed institutional practices and recommended changes.

But the 2021 appointee has also handled investigations with national profiles, such as the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers in 2020, the killing of Breonna Taylor by officers in Louisville, Kentucky, only a month prior and the beating and murder of Tyre Nichols in Memphis in January 2023.

Clarke says the allegations informing the Lexington investigation are both credible and numerous.

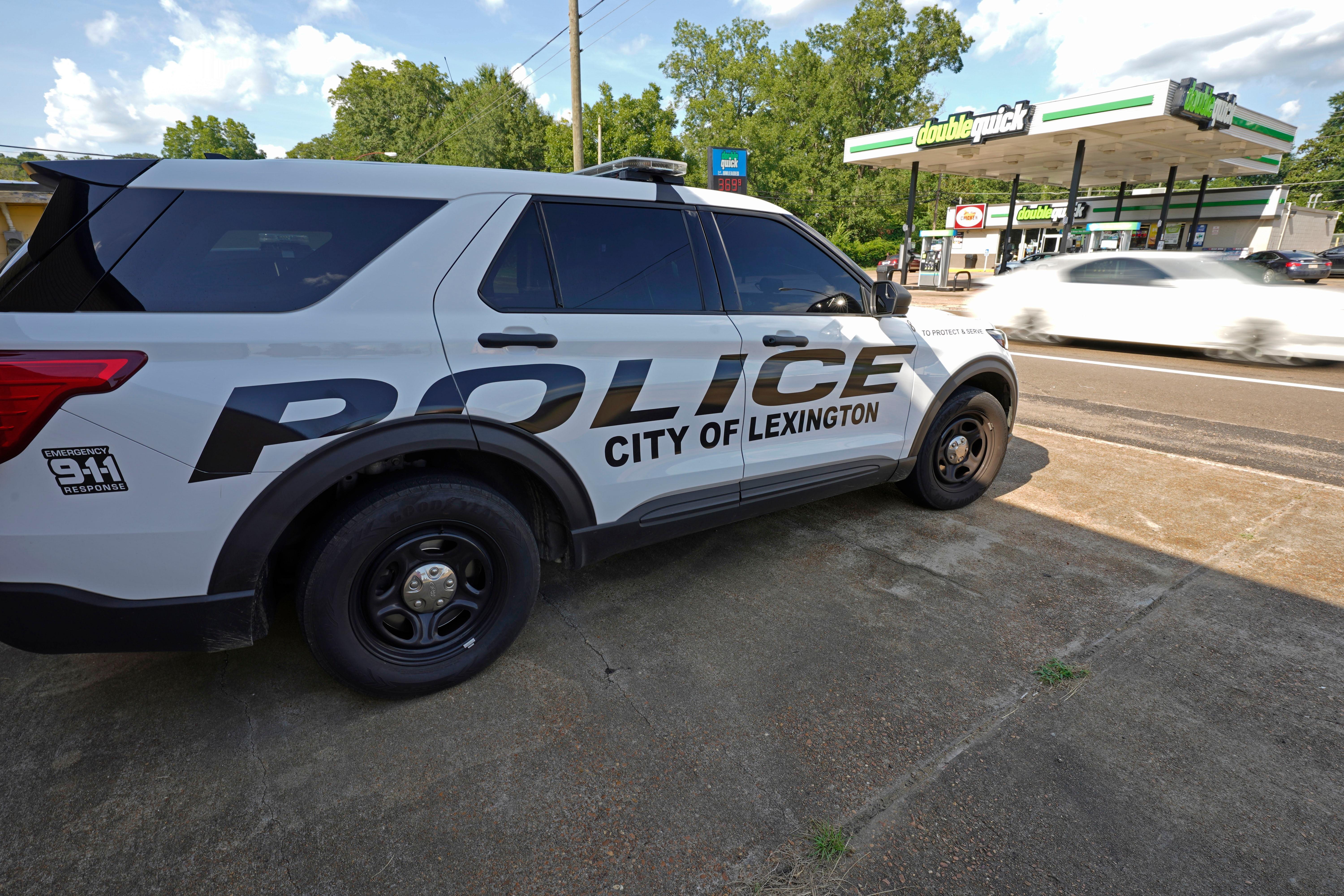

“There are allegations that Lexington police officers used illegal roadblocks targeted at Black drivers and retaliated against people exercising their right to question police action or record police activity,” said Clarke in the announcement at the Thad Cochran United States Courthouse in Jackson in November.

In addition to the city itself, this suit names Mayor Robin McCrory, former police chief Sam Dobbins and current chief Charles Henderson and demands millions of dollars in compensation for more than 20 plaintiffs, as well as an injunctive relief to put an end to the alleged pattern of policing.

Through what residents say has become a culture of violence, sexual assaults, racially biased policing, false arrests and excessive force, a fear of something as routine as traveling through town has become reason for some to move entirely.

In some cases, residents say certain officers facilitate the extortion of payments via third party means such as Venmo or CashApp in exchange for release from custody.

They also say a lack of certified officers on the force allows crime to go unchecked and often unsolved.

Continued complaints made to JULIAN organizers, Love says, show that even under active investigation that culture persists.

“What we see in other police misconduct investigations is that there tends to be an ebb and flow of police conduct – when the DOJ began their investigation in November, we did see a slight lull in police misconduct. Maybe they were adjusting to new parameters and where they could find time to commit abuse,” Love said.

“But after a while, they got right back up to their old issues. When the DOJ would stop riding along with them at 5 P.M. or wherever they weren’t being directly observed, they would just continue the misconduct,” he said. “The complaints that we've been getting have been that as soon as the DOJ isn't in the car with them or isn’t in the office with the police, they continue basically the same pattern.”

Current Lexington Police Chief Charles Henderson and Mayor Robin McCrory did not respond to a request for comment.