Residents of Lexington continue to demand police reform one year after former chief's firing

Michael McEwen

Lexington

For the past year a civil rights attorney and residents of Lexington, a rural town in the heart of majority-Black Holmes County, have been organizing against a police force they say operates under a culture of abuse and harassment.

About two dozen residents of the town of 1,500 gathered downtown last week outside the building which houses city hall, the municipal courthouse and police station. While half of the group was there for initial court hearings covering a wide range of traffic-related charges, the other half was protesting what they call false arrests by police and a violation of Black residents’ civil rights.

The protest was only part of a larger, year-long campaign organized by a civil rights attorney and residents of Lexington to demand change in both the police department and Lexington's government.

“It's ridiculous what our race has to go through. If you look around, you see no white people out here and this is every week,” said a resident who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution. “And so people of color really are having a hard time here. One thing I'm always asking myself is if there’s concern about the citizens of Lexington, because we have been through so much with the police officers.”

A majority of residents at the protest said issues began two years ago when former Lexington Police Chief Sam Dobbins was appointed to the position. Last July, only a year into his term, arecording surfaced of Dobbins bragging to a colleague about the number of people he’d killed in the line of duty while using racial epithets when referring to the victims.

The town’s board of aldermen fired him shortly after – but now a year on and with new chief Charles Henderson appointed, Black residents say a pervasive fear of traveling through Lexington remains.

“Oh, man, it's terrible here. Growing up here police were always nice and respectful, but now it's just out of control harassment and mistreatment,” said Chad Barnes, a lifelong Lexington resident. “They are afraid of the police, period. They are scared to drive in town. They are scared to go to different events and pretty much just scared to live in their own neighborhood.”

Barnes says that fear has hamstrung the ability of a majority of Lexington's residents to enjoy or feel a sense of community, and that he never expected that in his lifetime --following a deep history of Civil Rights action in Lexington -- he would feel the same duty to protest discrimination.

"Never in a million years did I think that. But with the things that we are facing here, it was more than right that I get in the fight and help the citizens, along with myself."

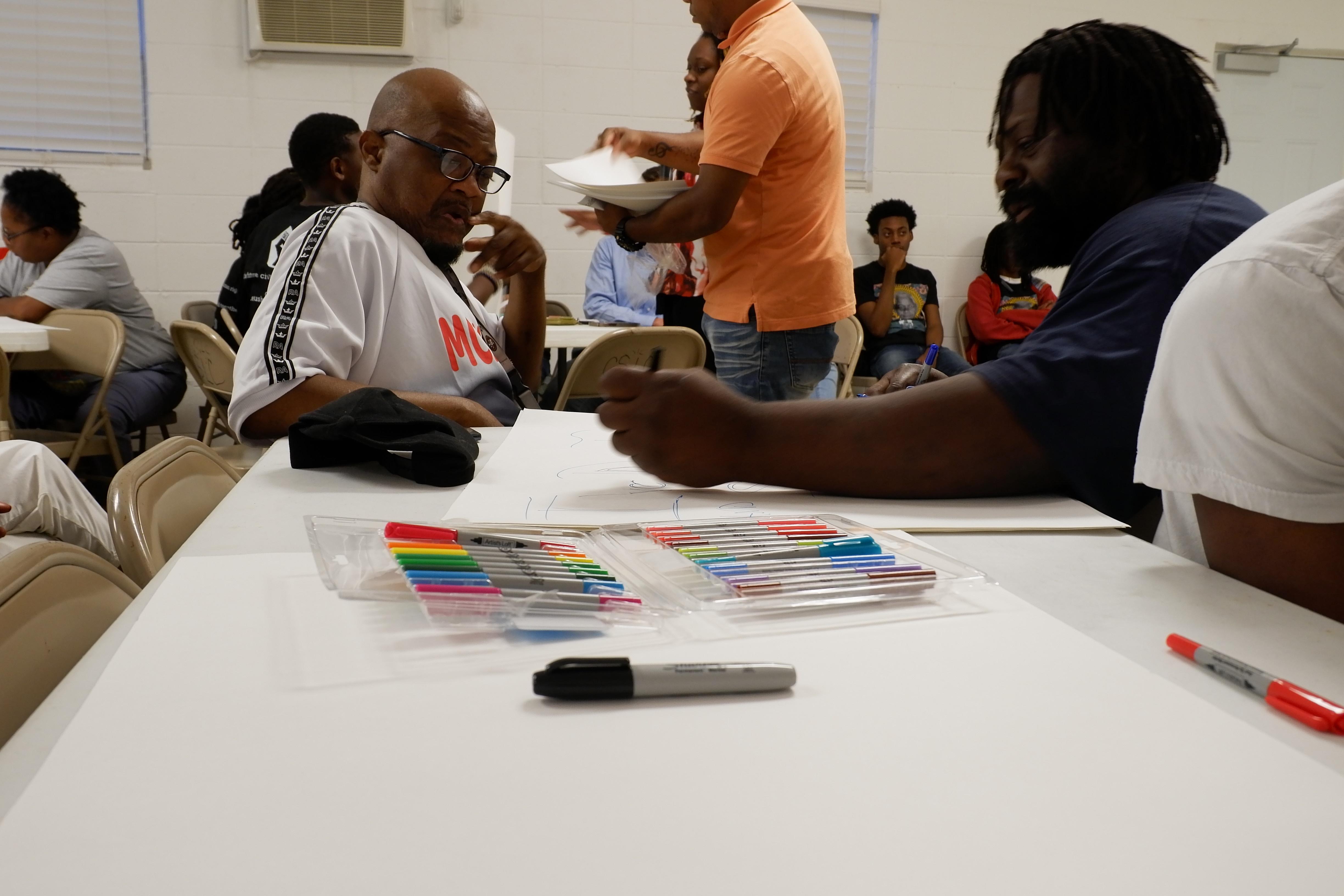

Since Dobbins’ firing last year, residents demanding change have met at an event hall only blocks from downtown every two weeks to plan future action and form a comprehensive list of demands: electing a new mayor and judges and hiring new, certified police officers chief among them.

According to multiple residents interviewed outside the July 12 meeting, traffic stops often turn into over-priced traffic citations and impromptu searches without a warrant.

Jill Jefferson, a civil rights attorney and founder of advocacy organization JULIAN, is providing legal representation to a number of residents recently arrested.

"Just like in the civil rights movement, meetings are so important to keep the momentum going, to keep the message out there to make sure that the strategy is permeating throughout the entire community," she said. "We get calls at 2:00 in the morning about police abuse here, when the cops are beating somebody up in that very moment and we have to respond. And so in terms of what it took, it really didn't take anything because we already knew what was going on."

The meetings, attended by well over 30 residents, typically begin in prayer and song and end in educating residents on their rights when stopped by officers. Particular attention is drawn to incidents where officers overcharge or overcite drivers for traffic infractions limited by state law, such as whether driving without proof of insurance is an arrestable offense or how much a ticket for not wearing a seatbelt should really cost.

In the first year of former police chief Dobbins’ tenure, according to data obtained by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, revenue generated for the city of Lexington through citations issued for not wearing a seatbelt, following too closely and disturbing the peace increased by more than threefold.

Jefferson says regular attendance by residents is an act of protest in itself.

“Coming to this meeting for people is a really brave act because the cops target people who come to these meetings. They drive by and they also park in the Dollar General parking lot, and they look at the cars who were here because it's a small town,” she said.

“They know who drives what car. And so after the meetings, in the days after and sometimes the same night, they start targeting people, arresting people for absolutely no reason, just because they came to this meeting.”

Among the demands for city hall to address the policing issue is also a desire for economic development. Like most towns in and surrounding Mississippi’s Delta, Lexington’s population has declined dramatically since the advent of mechanized agriculture and the end of Jim Crow Era policies, which saw large waves of outward-migration to manufacturing centers in the Midwest.

According to the 2020 United States Census, nearly 30% of Lexington residents live below the poverty line, a number which is more than double the national rate.

What was left is a much smaller tax-base and fewer opportunities for youth and the community at large – factors that make the price involved with those arrests much harder to bear. One resident at the courthouse said he was appearing for his initial court date while still without having his state issued I.D. returned by the arresting officer, now more than two months on from the arrest.

“I feel like your I.D. is something you're automatically supposed to get back, but when I bonded out they didn't bring it with my other belongings. I've been asking for it because I can't even get my job because I've got to wait on them to do something,” he said.

Only weeks after Dobbins was removed from his position unanimously by the town government, civil rights attorney Jill Jefferson filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi alleging Lexington’s police department had subjected Black residents to intimidation, excessive force and false arrests.

The federal suit names both former police Chief Dobbins as well as current chief Charles Henderson – Dobbins’ replacement – in addition to the city itself and the police department.

At its core, the lawsuit says the police department’s own pattern of behavior as well as city hall’s complicity in it is in violation of Black residents’ civil rights.

Last month, Assistant Attorney General of the United States Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division Kristen Clarke held a closed-door community session in Lexington which encouraged residents to speak up about abuses or harassment they’d faced by police.

Multiple residents with active complaints spoke, as well as Jefferson, who was arrested by the same police force she’s suing just days later for recording an ongoing traffic stop.

“It was no coincidence. It was nine days after the DOJ visit and also four days after I had formally complained about the police in front of Lexington's Board of Aldermen,” said Jefferson.

“After that meeting, I was talking to a well-known activist for about 30 minutes, and people affiliated with the police were driving by during that whole time. I said, ‘that right there is Agee, he's an investigator, he's assaulted several people.’ So they know what car I drive, and they know who I am here. So it's no coincidence that four days after that, one of the officers who arrested me is none other than Investigator Agee. That's what they do – they retaliate. One thing I don't think people realize is that if they do this to me, what are they going to do to people who are not attorneys, people who don't know what their rights are?”

Shortly after bonding out on misdemeanor charges of disorderly conduct, resisting arrest and failure to comply, Jefferson’s court date in Lexington’s municipal court was postponed because the judge – also named in Jefferson’s federal suit – recused himself.

Without a future court date set in Holmes County Justice Court, Jefferson says her arrest serves as an example of just how systemic the issue has become in Lexington, and in that way sets it apart from other similar cases of police abuse and corruption currently ongoing in other parts of Mississippi.

“One thing that sets Lexington apart from Rankin County and from Taylorsville is that this crisis has been quietly happening for two whole years – this is not new. This has been two years of this community being terrorized every single day,” she said. “This is completely unchecked -- the city is complicit in it. They're not doing anything to hold anyone accountable. They know about these complaints and they're making excuses for them. This community has basically been quietly going through this to the point where people are even afraid to speak up about what's happened to them because of the police abuse.”

'They're just as guilty as he was'

Among the pattern of traffic stops, according to residents, is also a concerning rise of violent encounters with officers.

Formal complaints over the culture of abuse and harassment in the police department have reached current Chief Charles Henderson, who was initially hired during Dobbins’ tenure and has been named by several residents as a perpetrator of several beatings and false arrests.

Lexington native Leroy Seacrest, who spoke at the U.S. Department of Justice's community meeting in June, said he was charged with disturbing the peace and beaten by current chief Charles Henderson and detective Aaron Agee only days after he accosted the latter for beating and dragging a mentally ill woman through a downtown street.

According to Seacrest, officers contacted him on his cell phone to notify him they'd blocked in his 18-year old son and several friends in their parked car at a town basketball court. They claimed the boys were drinking alcohol while seated in the car, but Seacrest said there was none when he arrived. After he clarified his son wasn't being arrested, Seacrest was preparing to leave when Chief Henderson called his attention to the incident downtown days prior.

"He asked me if I remembered that incident with the girl, and I told him I did. So we were just standing there, my hands were in my pockets, and that's when Agee ran up to my side and threatened me with his taser. I told him I wasn't doing anything, and then he slammed me to the ground and arrested me," said Seacrest. "It was the chief and the same two officers who did everything when Sam Dobbins was still here. When they got rid of him, they still kept them and I just don't understand why. They're just as guilty as he was."

Another target of the now year-long protest campaign has been the hiring of new, certified police officers to replace those currently uncertified but who still work for the department. While two officers of the force of less than 10 were recently fired due to a lack of proper certifications required by state law, residents say hiring practices across Holmes County municipal police forces ensure that officers fired from one department can easily move to another.

Some also worry that Dobbins himself continues to exert influence over officers working in Lexington.

"They will get fired in one city and come to another city where they know they can get hired because the police departments here run the same way. So you can get fired here and go maybe ten miles up the road and get hired at the next one," said Barnes. "And I think Dobbins is in the background. Even though he doesn't work for the Lexington Police Department anymore, he still has his hand in telling them what to do."

Several complaints have also been filed against current police chief Charles Henderson himself in the year since he took the position. He is also named in the federal lawsuit filed by Jill Jefferson, who is skeptical of the town government's due diligence in his hire and says it's emblematic of a much larger issue in the Mayor's office and Board of Aldermen.

“Dobbins replacement Henderson is no better. Henderson has had so many issues with sexually assaulting women -- they knew that before they hired him because there are cases that people filed against him before that,” said Jefferson, who is also handling one of the two complaints filed against Henderson in court. “We know just a few months ago, Henderson choked the only female officer on the force in the station. We have a woman who gave us an affidavit talking about how Henderson held her hostage in her home for an hour and sodomized her. So this situation, it's not any better.”

Lexington Police Chief Charles Henderson, Mayor Robyn McCrory and the Board of Aldermen could not be reached for comment.