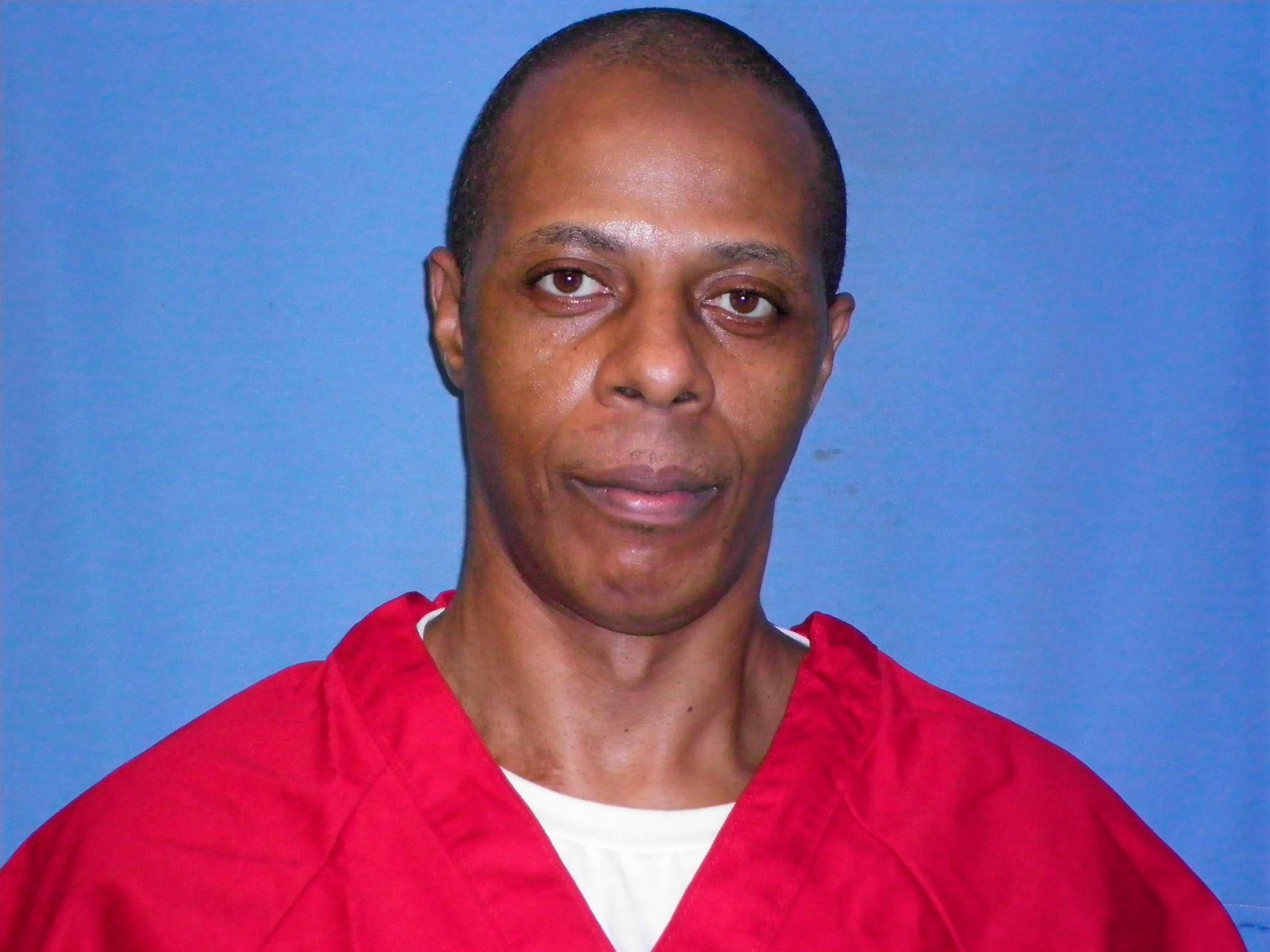

Michael McEwen:Willie Jerome Manning was convicted in 1994 for the robbery and murders of two Mississippi State students in Starkville in 1993. On November 9th of this year, Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch filed a petition to have a stay of execution that was issued for him removed and to have an execution date set. Where does his case stand now?

Krissy Nobile: Prior to the state moving to set Manning's execution date, we actually filed on behalf of Manning, along with Manning's long time counsel, in a petition for post-conviction relief that reasserts his innocence. His innocence is something that Manning has asserted really at every step since he was arrested in 1993. So even prior to the state's motion to set an execution date, Manning had a petition for post-conviction relief filed. The Mississippi Supreme Court, basically held the motion to set an execution date in abeyance -- which just means it's stayed -- and told the state that it needed to respond to the previously filed petition for post conviction relief. So the state is required to respond to our petition by December 29th.

Michael McEwen:What's the main argument in his petition for post-conviction relief? What are some of the claims that he and that your office are making that the state should reconsider?

Krissy Nobile:Manning has basically newly discovered evidence related to recanting of key witnesses that were essentially what people think of as jailhouse snitch witnesses, as well as scientific developments. Manning has also provided new expert analysis, as well as concessions from the FBI, about the FBI's prior fatally flawed hair analysis, ballistic and forensic evidence that the state relied on to convict Manning. We also have evidence now that witnesses have admitted that their testimony was fabricated in exchange for favorable treatment from the state, and that included money and sentence reductions. And those are sworn affidavits that are attached to Manning post conviction petition. So really, the kind of key things that were used to convict Manning were these hair analysis and ballistics analysis from the FBI. The FBI itself has admitted that its analysis was false. And also these so-called jailhouse snitch witnesses who have now recanted.

Michael McEwen:As I understand, the hair analysis that the FBI conducted couldn't really scientifically determine that it was indeed Willie Jerome Manning's hair that was found in the car where the two Mississippi state students were held. They just they described it as African-American hair, and that's how they made that determination that it must be Willie Jerome Manning who killed them. Could you explain that?

Krissy Nobile:That's right. There's not any physical evidence connecting Willie Manning to this crime. There's no fingerprint evidence, there's no DNA evidence. There's no blood evidence and there's no fiber evidence. And what the prosecutor relied on was a hair that the FBI at that point said came from a black person. And the FBI in 2013 recanted that and said that conclusion goes beyond the limits of science, that that's basically what we consider in the mainstream to be junk science.

Michael McEwen:I'm curious about the time component of where Manning's case stands now. Of course, it dates back to 1994, but in early November of this year the Mississippi Supreme Court granted a time extension for the state to review and respond to Manning's petition. And about a week and a half later, Attorney General Lynn Fitch filed motions on the state's behalf to have an execution date set. Are you aware of any reasoning as to why the Attorney General filed motions at that time?

Krissy Nobile:I am not. They do what they think is best for them and we respond in turn. I do think it's a little bit curious to file an extension of time saying that you need more time because the petition is lengthy and you need to need more time to have a meaningful response. And then at the same, right after that, file a motion to set an execution date. That is a little curious timing, for lack of a better word, but I do think that executions in general just are not the place to be acting first and asking questions later. And so I am very appreciative of the fact that the court is at least requiring the state to respond to this petition.

Michael McEwen:The deadline for reviewing Manning's petition is December 29 of this year. After they do review it and consider it, what is what is then actionable on the state Supreme Court's behalf? Will they look to maybe a retrial or striking the convictions? What would that look like?

Krissy Nobile: After the state responds, we will have a chance to do what is referred to as a reply brief. After that, it will be fully briefed up and the Mississippi Supreme Court will consider the legal arguments. And just for post-conviction petitions in general that start with the Mississippi Supreme Court, which all death penalty cases do, the Mississippi Supreme Court can grant relief. They can say the legal arguments satisfy the law and we are reversing Manning's conviction. The District Attorney in Oktibbeha County could then retry him. Or they could say, no, this doesn't satisfy the law, and deny the petition. Or they could do what they did in Manning's other case and say there are some arguments here that need factual development, so we're remanding this case to the circuit court to have an evidentiary hearing. And at that point, the circuit court will be looking at the arguments, seeing witness testimony, considering evidence, and then deciding where to go from then in terms of reversing Manning's capital murder conviction.

Michael McEwen:I'm wondering from your perspective as an attorney, how does the process look to try and and argue a case like this well after the fact. To get these ideas across that these people were influenced and the sheriff was really pushing for a conviction -- how difficult of a task is that?

Krissy Nobile:Post-conviction is always difficult because you're coming in after trial and after what people typically think of as an appeal. And that's where you just go up from the trial court and you're limited to the record and you're basically arguing over the law that doesn't go beyond the trial. In post-conviction you're allowed to go beyond what happened at trial. So that's always hard because a lot of things have happened in 30 years. But I do think that there is a lot of evidence completely undermining Manning's conviction and proving that he may, in fact, be innocent. And that's what that's what post-conviction is for, is to look at errors that are inherent in our criminal justice system because it's a human system.