Nationally, homicide is ebbing from a pandemic-era crest.

Analysts celebrated a projected murder decline of more than 10% across the country earlier this fall. In the South, cities such as New Orleans have enjoyed dramatically declining murder rates.

But that makes regional hotspots more perplexing for some communities. Baton Rouge homicides are trending upward, and Birmingham has seen tragic events such as two shootings on one July day in which a total of seven people died, including a five-year-old Black boy.

The deaths have stirred angst among city leadership, especially Mayor Randall Woodfin, who has spoken out in frustration about the violence and called for stronger gun-control rules.

Woodfin has lost family members to gun violence, reports say.

“Right now my mind is on the families who are experiencing a sudden, giant void in their lives,” he wrote on Facebook following the Five Points South mass shooting. “The children who are experiencing loss and grief far, far too soon.”

Chris Anderson, a Talladega College police chief, retired Birmingham homicide detective and former reality TV personality, said he’s seeing something different with this year’s gun violence in Birmingham. Lesser crimes like burglary aren’t rising in tandem with the homicides affecting young men.

To him, that means there is an answer to what’s happening, and new approaches are needed.

“It’s going to take much more than just policing,” Anderson said. “It is going to take a connection between the community and police and our business partners and a lot of the people that can come in and offer some outside help.”

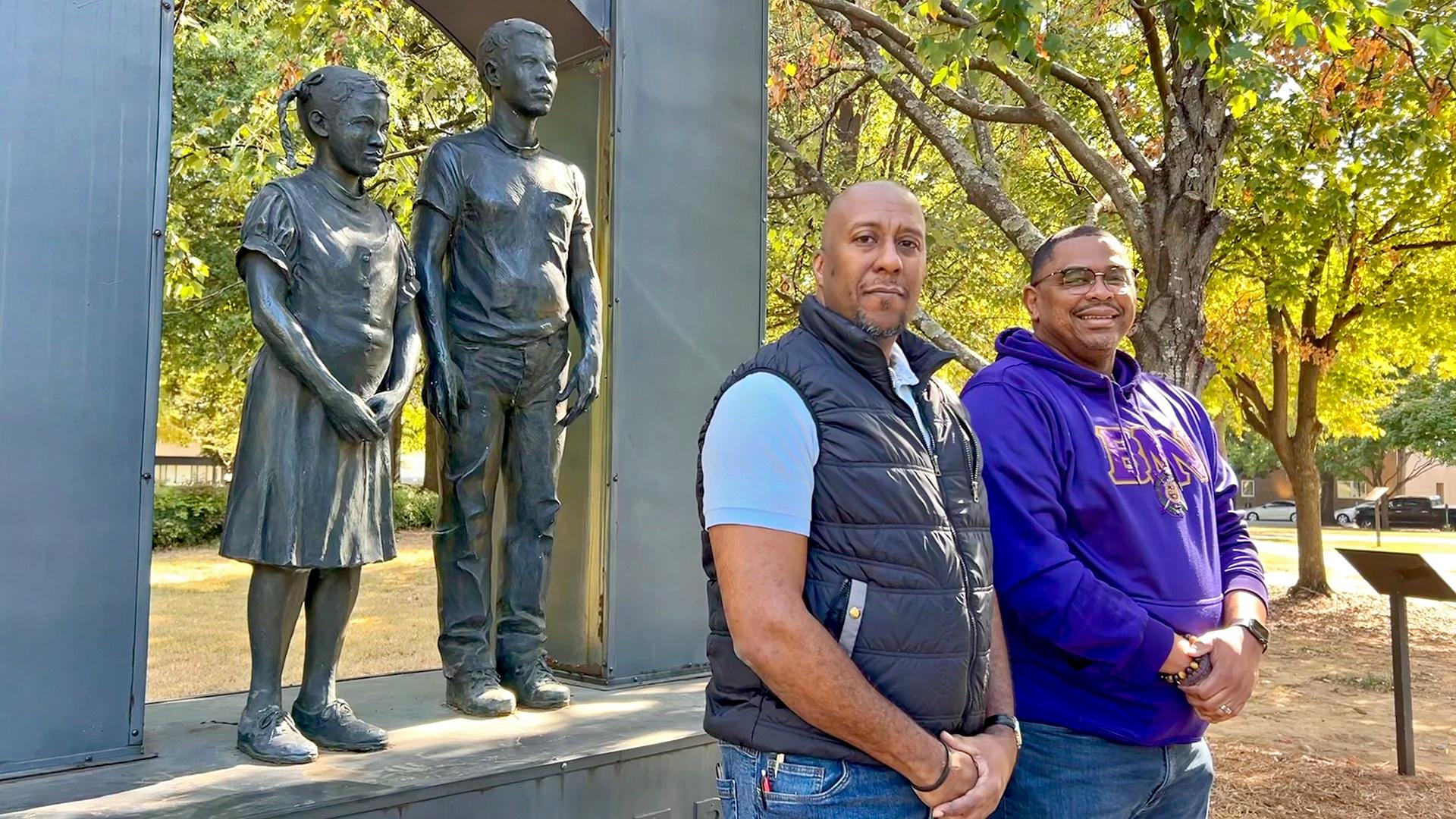

Anderson and a friend, Lamar Lawrence, are involved with 100 Black Men of Metro Birmingham, which mentors young men — mostly of color — through college age. The group is a local chapter of a national, civic-minded organization.

Lawrence and Anderson said their members have found that young men’s lives are steeped in social media videos that sometimes glorify violence. Most of them, they believe, just long to be part of something bigger than themselves.

“That’s why gangs are so successful. They’re like families,” Lawrence explained.

Mentoring can “break the cycle of crime before it even begins,” Anderson said. The group hopes to demonstrate alternative pathways for younger people, giving them options beyond what’s outside their front door.

For now, chapter members will be thinking and praying about how they can help with the violence affecting young men in their city.

“I’m a Black male, but we can kind of become numb, or this compassion fatigue can kind of set in,” Lawrence said. “I think that’s the thing that we have to fight against.”