Williams said Hurricane Katrina was a big turning point in the way New Orleans approaches drainage and flood solutions.

It led city leaders to start a series called the Dutch Dialogues, where they talked with Dutch colleagues about how they live with water.

“That led to a plan back in 2013 called the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. The whole idea behind it was living with water. How do you live with water as an asset versus as an enemy?” Williams said.

Williams said her office is in the process of doing drainage studies to better understand New Orleans’ drainage system. The city wants to have a data-driven approach that aligns with community efforts.

“We are working with a couple of community agencies to think about how we re-envision some of the spaces that people use often, and make sure that we are addressing the flooding issue in some of these neighborhoods,” Williams said.

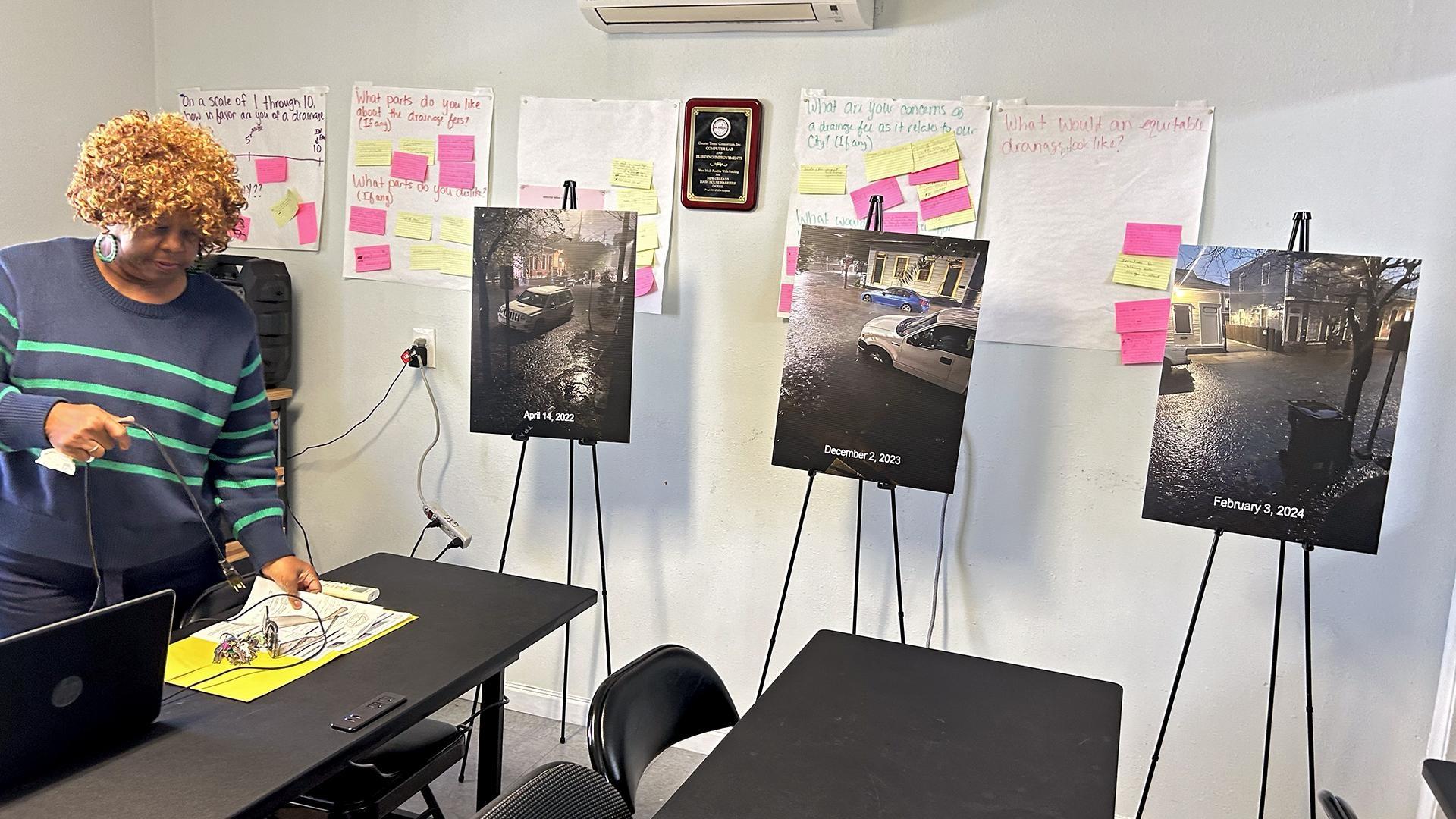

Back in Treme, Cheryl Austin shows some final examples of green infrastructure, like the rain gardens and planter boxes to hold water. The Greater Treme Consortium has partnered with groups like Water Wise Gulf South to implement more of it.

They also took inspiration from a trip to Amsterdam to study and figure out what they were doing to prevent flooding.

“What I took away from that in order for them to be successful, with flood prevention, is that everyone is incorporated into the process, the grassroots people, the organizations, the corporations, the residents, the government,” Austin said.

Meanwhile, the consortium and its partners hired an engineering firm to help them identify why flooding persists in some street corners, like Dumaine and North Robertson. Austin said they should have more information by the end of May.