The miners demanded better pay and benefits, but the origins of this strike are tied to the price of steel.

That’s because the coal taken from these mines in Brookwood, Alabama isn’t used for energy but for making steel. In 2015, the price of steel plummeted, ending the year 44% lower than the previous year. This led the company that operated these mines at the time, Walter Energy, into bankruptcy The mines’ debt holders then formed a new company in 2016 called Warrior Met Coal to take over.

According to the miners, Warrior Met told them that it needed to cut their pay and benefits in order to keep the mines open, and the company would look into restoring what they lost after five years. Warrior Met, however, denies making any promises to them.

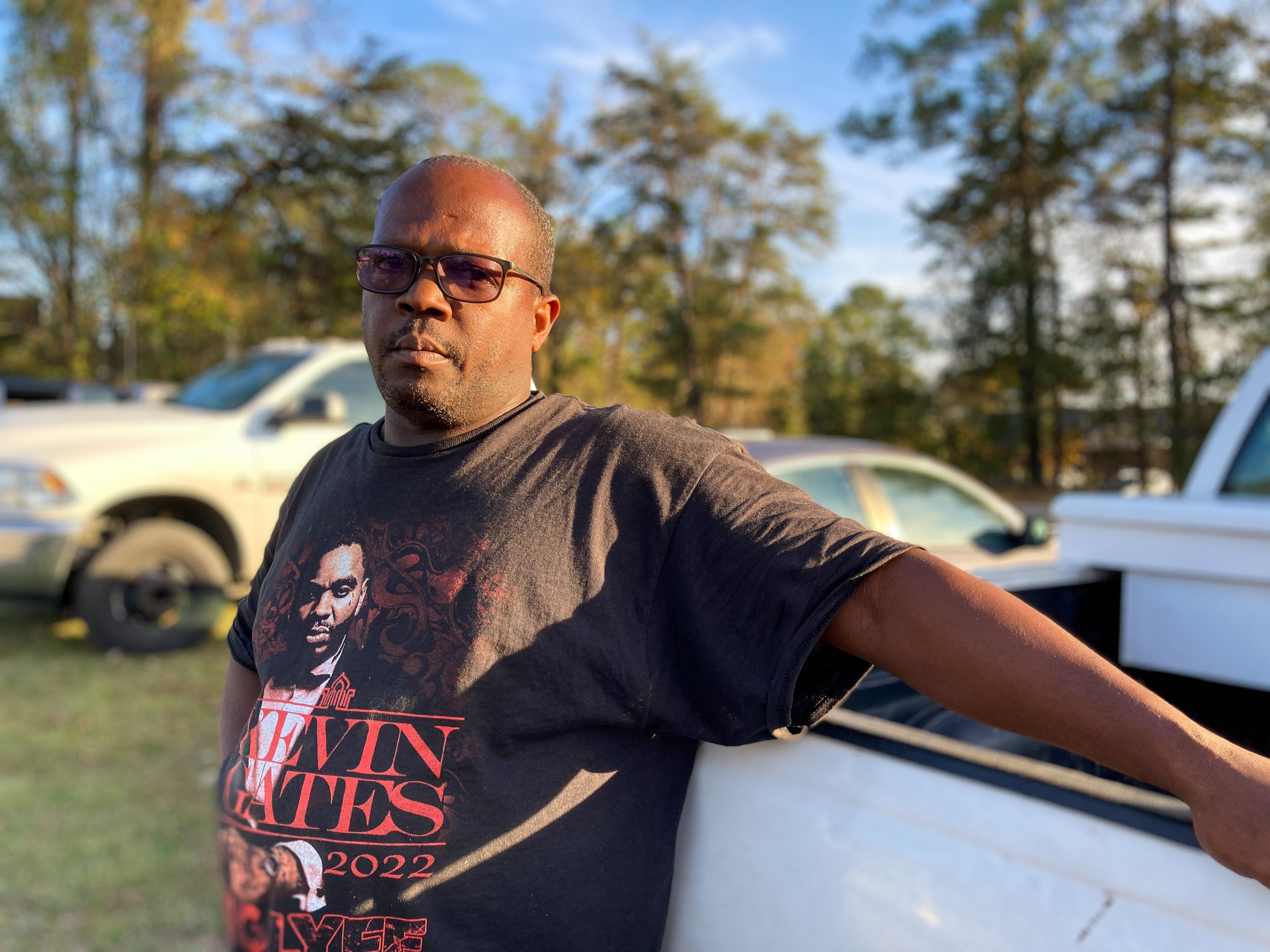

After those five years passed, Warrior Met offered a roughly 11% raise to the miners, but many said that wasn’t enough; Miner Rily Hughlett said his pay was cut about 14%, but the strike was about more than just money — they also wanted more vacation time and lenient sick days.

“Even on Easter they would have us come to work,” Hughlett said. “We should have Sunday off anyways. I go to church on Sunday.”

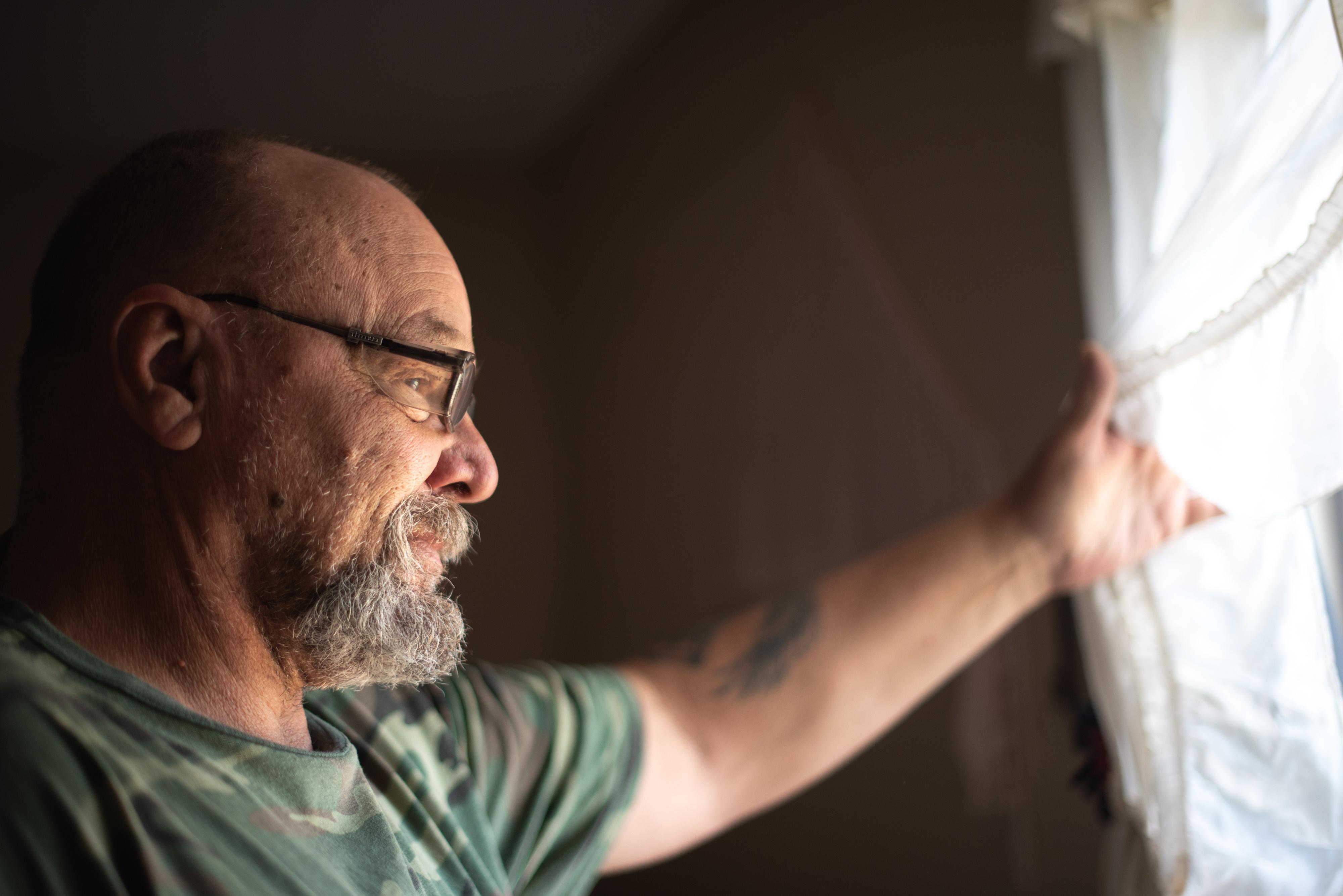

On April 1, 2021, roughly a thousand miners officially went on strike. Miners regularly formed picket lines outside the many entrances to the Warrior Met Coal mines, stretched out over dozens of miles weaving through the backwoods of Brookwood. Miners set up grills and built makeshift shacks to protect themselves from the sun during the long hours they would be protesting. They joked together on lawn chairs between the mine’s shift changes to pass the time.

But the strike was also marked by violence. The UMWA accused replacement workers of trying to hit miners with their cars. Warrior Met Coal later released an edited video, just under four minutes long, that appeared to show multiple scenes involving miners tossing a cement block through a car’s rear window, swarming a bus full of strikebreakers and the presumed aftermath of fights that left the faces of workers bloodied. A separate video showed security camera footage of a fistfight.

A federal judge in November 2021 banned the strikers from picketing outside the mine entrances after Warrior Met cameras recorded miners attacking workers’ vehicles. The union agreed to pay $435,000 in damages to Warrior Met last fall.