Before Alan Miller became the nation’s second-ever person to be executed by nitrogen gas, men living on Alabama’s main death row met to discuss how to stay calm.

That’s according to Esther Brown, the executive director of Project Hope to Abolish the Death Penalty, a group led by incarcerated organizers. Brown’s phone rings every day with calls from people who are imprisoned and sentenced to death.

She said their mood was “very upset, very uptight,” as Alabama readied to use the novel method to put Miller to death — while keeping on pace toward the state’s busiest year for executions since 2011. The Yellowhammer State is set to lead the nation in executions this year, data from the Death Penalty Information Center show.

“Of course, we’re not doing well,” Brown said. “You know, it’s just — incomprehensible.”

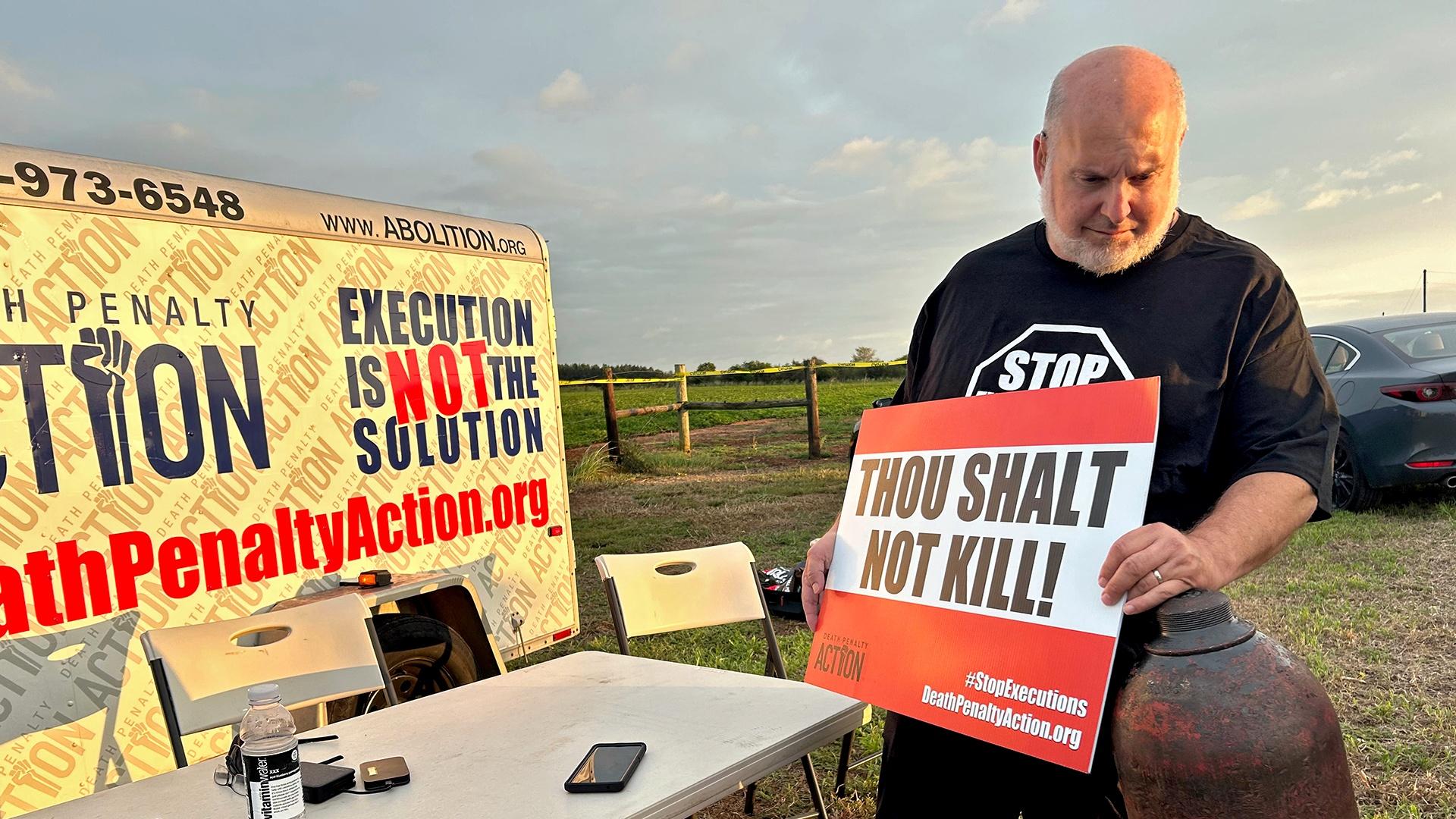

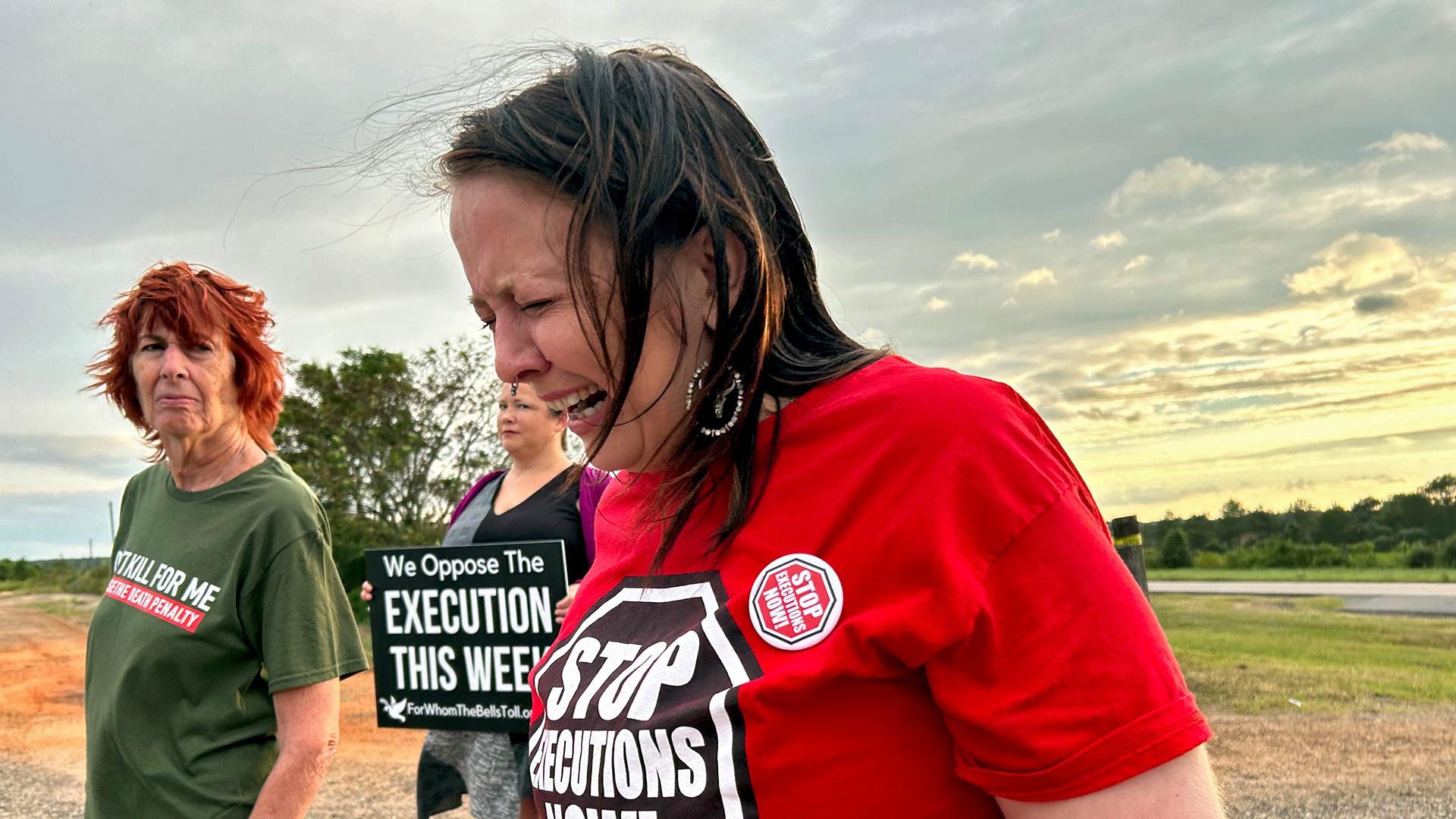

Alabama followed through on its plans to execute Miller on the evening of Sept. 26, in a move that stoked outrage and grief among death penalty opponents. It also raised questions about the possible future of the controversial execution method in the Gulf South, while underscoring Alabama’s increasingly atypical use of capital punishment.

Alabama remains the only state to have tested out the nitrogen gas method, but Mississippi, Louisiana and Oklahoma have legalized its use, according to reports.

As Alabama sets this new course for execution methods, William Berry, a law professor and associate dean at the University of Mississippi who often writes about capital punishment, said its eyewitness accounts show the nitrogen gas executions are “way more draconian and brutal” than imagined.

“It seems much more like the same kind of problems you had with electrocution, in terms of this brutality and unintended consequences,” he said. “I wonder the extent to which this will really catch fire and states will start doing this regularly, or not.”

Berry said nitrogen gas executions came into play in response to the availability of and challenges to drugs used for lethal injections. He added that other scholars have written that injection protocols were developed in part because of unpleasant effects — such as smells of burning flesh — related to the electric chair.

In January, Alabama’s attorney general touted nitrogen gas, saying that its “proven method offers a blueprint for other states.” He reaffirmed his stance in a statement after Miller’s execution. His staff didn’t fulfill a recent interview request.

“Tonight, despite misinformation campaigns by political activists, out-of-state lawyers and biased media, the State proved once again that nitrogen hypoxia is both humane and effective,” Marshall’s statement said that night.

“Miller’s execution went as expected and without incident.”