Sometimes those objects or human remains found in graves are used in scientific research for studies that haven’t been approved. In many cases, they weren’t donated to science but were taken instead.

Whether it’s an object dug up by a private collector or part of an archeological dig — the end result is the same.

“Once it’s gone, you can’t get it back. And cultural resources are nonrenewable,” Panther said. “So if they’ve been destroyed or collected, you know, not only does that not provide any cultural context for tribes, for interpretation and knowledge, but it’s just gone.”

Panther said she and her colleagues have been trying to get state institutions to instate research moratoriums once they start the NAGPRA process. She also wants more institutions to ensure they include Native American people in the process because NAGPRA isn’t just about following a federal law — it’s a human rights issue.

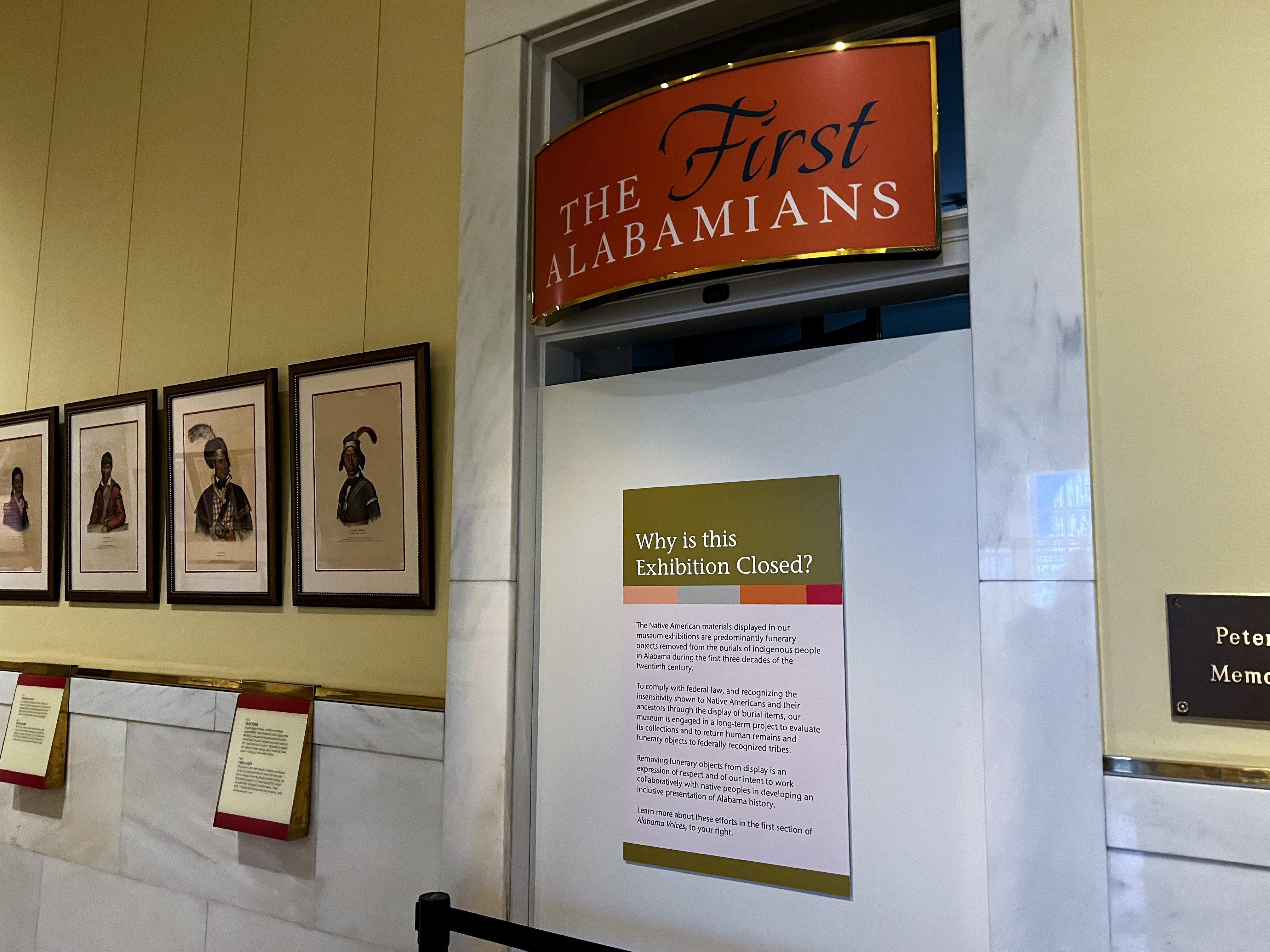

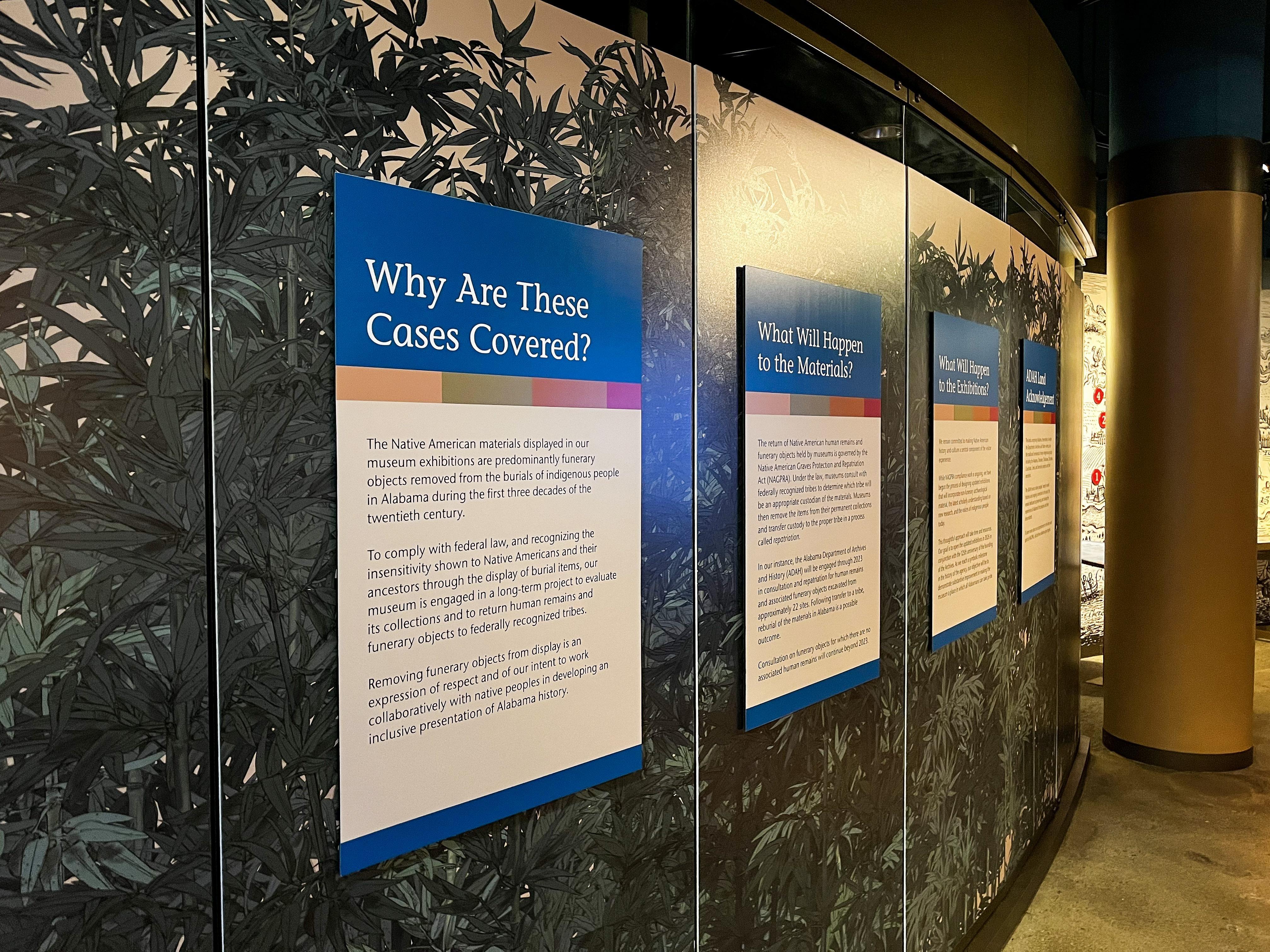

“I really think that we’re turning the tide in the professional realm of getting more people on board with taking objects off display, making sure that research isn’t occurring without the appropriate tribal people’s permission, and really moving towards not only being compliant with NAGPRA, but even being proactive,” Panther said.

What the Alabama Archives is doing is a good example of what should happen across the Gulf South, Panther said. What are now Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana are the ancestral homelands for many Southeastern tribes, but most of those tribes were forced to move further west during the Indian Removal Act.

“I think that [Alabama will] probably always be one of those states simply because they were a huge landmark for us in our homeland,” Deanna Byrd, the NAGPRA coordinator for the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma who has worked with the state of Alabama for years, said. “So, you know, Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama will probably always remain open because we work with federal agencies on a regular basis down there.”